From Abracadabra to Zombies

Superstition and Fun in Mexico

Candelaria 2008 by Robert Todd Carroll

In half a day we, the Superstition Busters of

America, traveled from our cold, rainy, sleeping village in northern California to the tropical world of Tlacotalpan, nestled on the banks of

the Rio Papaloapan (the river

of the butterflies), where upon our arrival a torpid village of some few thousand

would transform into a frenzied party of dancers, singers, drinkers,

vendors, jaraneros,

mariachis, bulls running wild in the streets, fireworks at all

hours of the day or night, a morning parade of hundreds of children

wearing school uniforms and carrying effigies of bulls and tall

ladies, processions of equestrians in colorful attire,

and supplicants carrying a statue of the Virgin Mary from a church

to a boat for a ride up and down the Papaloapan in hopes that she

will keep the waters calm. The two-week

festival is called La Candelaria, but the heart of the

activity occurs over three days, from January 31 through February 2.

And we were there to take it all in and cleanse the area to make it

safe for skeptics. For a religious festival, however, the place was

writhing in secular fashion from the moment of our arrival. There

was a lot of stuff to be sold, a lot of money to be made, and a lot

of fun to be had if you were careful. (Photos of the party:

here and

here.)

uniforms and carrying effigies of bulls and tall

ladies, processions of equestrians in colorful attire,

and supplicants carrying a statue of the Virgin Mary from a church

to a boat for a ride up and down the Papaloapan in hopes that she

will keep the waters calm. The two-week

festival is called La Candelaria, but the heart of the

activity occurs over three days, from January 31 through February 2.

And we were there to take it all in and cleanse the area to make it

safe for skeptics. For a religious festival, however, the place was

writhing in secular fashion from the moment of our arrival. There

was a lot of stuff to be sold, a lot of money to be made, and a lot

of fun to be had if you were careful. (Photos of the party:

here and

here.)

The highlight of the festivities is called El Paseo de la Virgen de la Candelaria. In Tlacotalpan, it involves several superfluous but impressive rituals aimed at appeasing the river, an act made unnecessary by the building of a dam several years ago. Fear of flooding is no longer an issue, but on February 2nd, which is apparently the birthday of the Virgen de la Candelaria, a mass is held at dawn with mariachi and jaraneros playing and singing Las Mañanitas (the Mexican birthday song). (I must admit that I slept through the morning festivities.) That afternoon the statue of the virgin is taken from the church to the river, where it is carried to a barge that takes her for a short ride upstream and returns flanked by dozens of little boats full of spectators. Our party watched the nautical procession on Saturday afternoon from the patio of our hotel, Casa del Rio, where we sipped cerveza and other adult beverages, and took obligatory photos of the ceremony.

The Fiesta de la Virgen de la Candelaria is celebrated in various Hispanic Catholic countries besides Mexico, including Bolivia, Chile, Peru, Venezuela, and Uruguay.* Brittany Spears may be big business in the U.S. but the Virgin Mary is bigger south of the border.

We chose the Tlacotalpan fiesta because a friend had been to the town before and found it charming. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, known mostly for it colorfully painted neoclassical buildings.

Don't be deceived. There is a lot of poverty here. (Click here for more photos)

The town features two Catholic churches, one for the poor (the Iglesia por San Cristobal) and one for the less poor. They're located not more that a football field apart, separated only by the zocalo or town square. The exterior of the poor church is rather beautiful, but inside the church is rather plain.

The church of the Virgin of the Candelaria is colonial and much more elaborate inside. All through the weekend the doors of the Virgin's church were left open, so the people inside praying or meditating could enjoy the warm breezes and the rhythmic sounds of the jaraneros outside. A local historian informed me that not that long ago, the same Catholic church would have suppressed this music and dance that surrounds the church during candelaria. The music and dance originated in Spain, was kept alive for centuries by descendents of slaves from Africa, and was resurrected in recent years and claimed as the traditional music of Veracruz and Tabasco. One song from this tradition has made its way to the pop charts in the U.S.: "La Bamba," a hit for the young Ritchie Valens in 1958 and for Los Lobos in 1987 when it was recorded for the movie about Valens and his short career. He died in a plane crash in 1959 along with Buddy Holly and The Big Bopper (disc jockey, J. P. Richardson). Unfortunately, I'm old enough to remember it as if it were yesterday.

On Friday, the day before the Virgin's birthday celebration, we sat on the curb of the riverfront road and drank cerveza while watching the performance of the voladores or flyers. They pass the hat and then when the crowd has put in enough pesos to make it worth their while, the last of the flyers climbs a tall pole (about 125-150 feet high) and joins several comrades for a descent to earth while spinning around the pole and gradually lengthening a rope attached to their ankles. One fellow stays at the top and plays the flute while the others descend. Somebody else beats a drum. The act is a traditional act of worship, apparently originating as part of a set of rituals to appease the fertility god so that he might send rain, end the drought, and provide food for the people's survival. It must have worked. Totonac men have been doing this for centuries and they're still here.

After watching the voladores perform, we

boarded a boat and awaited the bizarre custom called El Corrido de Toros.

About a half dozen bulls are dragged from their pens across the

river and one by one are forced to swim to a small

sandy bank in town where they are released to wreak havoc on anyone

who gets in their way. There is some taunting and jeering, as the

bulls stumble up the bank and make their way to the street where

ambulances await to take the injured to the local hospital or

heliport to be flown to Veracruz.

their pens across the

river and one by one are forced to swim to a small

sandy bank in town where they are released to wreak havoc on anyone

who gets in their way. There is some taunting and jeering, as the

bulls stumble up the bank and make their way to the street where

ambulances await to take the injured to the local hospital or

heliport to be flown to Veracruz.

I was told that this year the gathering of some 50,000 or more was small because the festival coincided with Carnaval, which is celebrated in nearby Veracruz city on a level comparable to Rio de Janeiro. Two relatives of our hotel manager were injured by the bulls, along with about thirty other people. Her niece had come down from Mexico City to help at the hotel for the weekend, but she was gored while looking for a pair of sunglasses at a rack put up by one of the vendors in town. She was still in the hospital when we left on Monday. The manager's uncle was walking home when he was lifted by a bull and thrown in the air. He ended up with a broken collar bone. We heard from an American who lives in town that two people were killed by the bulls this year. By chance, we happened to be in a boat on the river watching the transfer of the bulls and seemed to be out of danger. Were we guided there by some protective spirit? Probably not, but I was very glad to be on the water rather than on the river bank where I had been an hour earlier.

The day before the bulls ran most businesses in town were putting up bamboo and wire barricades. While the barricading was occurring we took a boat ride and at one point pulled in to the place where the bulls were being kept. We got up close and personal with a group of Brahman bulls, sacred in India but bred for their delicious meat in this part of the world. These are not fighting bulls and the run is not like that in Pamplona, Spain. I got conflicting stories about what happens to these bulls once they have finished their day in town. Some say they are butchered; others say they're taken back to their pen and then butchered after a little more fattening up. Either way, they end up hanging in a butcher shop in the mercado.

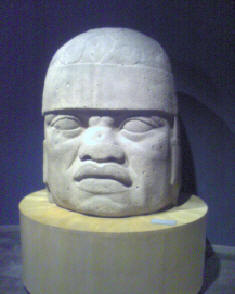

On the bright side, this is Olmec country, where three thousand years ago a people emerged, gradually expanded into a civilization that lasted for over a thousand years, and then vanished. Little is known about the Olmecs, but they left behind a number of artifacts, most notably colossal sculptures of heads, each with its own distinct features, perhaps representing different rulers. The ancient Jews were still tending their flocks when the first of the great Mesoamerican civilizations was emerging. Christianity was just starting to replace the pagan religions of Rome when the Olmec world

vanished, to be buried in the jungle until 1862 when the first giant stone head was discovered in Veracruz. In 1939 more discoveries were made and it eventually became clear that the Olmecs were distinct from the Maya and that the Mayan civilization was not the mother culture of Mexico but in fact borrowed much from the Olmecs.*

It may surprise the doomsday folks and their fearful followers that not even the Maya seem worried about a catastrophe

when the cycle of the current

Mayan calendar ends

and a new one begins in 2012.

followers that not even the Maya seem worried about a catastrophe

when the cycle of the current

Mayan calendar ends

and a new one begins in 2012.

In the Museo Nacional de Antropologie in Mexico City, one can see a display of a ball game court used by the Aztecs. The game involved hitting a large rubber ball with one's hips and trying to put it through a circular disc on either side of the court. Apparently, the Aztecs awarded the winner by sacrificing him to the gods, since the gods don't like losers. Or something like that. The people we call the Aztecs lived in Olmec country and beyond about one thousand years after the Olmecs had disappeared. The Aztecs gave us the word 'Olmec', which means "rubber people" in the Nahuatl language. The Olmecs apparently tapped their rubber trees and mixed the latex with the juice of some plant to make rubber balls or at least the Aztecs thought they did.

It was the Aztecs who were ruling when Cortés and his Spanish conquistadores arrived with their guns, germs, and steel. Those who have read Jared Diamond's brilliant book of that name know why the Spanish could easily conquer the Aztecs despite their ferocity and bloody practices, such as human sacrifices to their gods. Even today there are remnants of those times. Go into any church in Mexico and you will find a representation of a Christ crucified who is splashed with blood from head to foot. Legend has it that these bloody depictions of a slain god-man made it easier for Christian missionaries to convert indigenous peoples who were accustomed to bloody sacrifices to appease gods. The job couldn't have been too hard in the beginning, though, since the Aztecs identified their leaders with their gods and would need little persuading that the conquerors' god must be more powerful than their own.

Mexico does not differ from any other Christian country where people call anything good and unexpected a miracle. The day after I returned home there was a story in the local newspaper about a 'miracle' that happened. A young girl had been in a coma after an accident and she came out of the coma. The family was very happy that this miracle happened and they thanked god for it. Of course, god was not blamed for the accident or the coma, and had she died, it would have been god's will and for some good purpose. The human mind has a wonderful capacity for self-deception and framing things in ways that make things that happen for no particular reason seem to be guided by benevolent and purposeful forces. Such thinking provides comfort. Others strive to please their Lord by making themselves uncomfortable. Go figure.

Outside

the modern basilica that now holds the painting known as "Our Lady of

Guadalupe," people make their way across

concrete on their knees to ask for miraculous

cures. Inside, masses are

continuously said and people come from all over the world to ask for

intercession to cure their cancers or crippling arthritis. Next to

the basilica stands an older

church, a reminder of colonial days and styles, that is sinking

badly on

Outside

the modern basilica that now holds the painting known as "Our Lady of

Guadalupe," people make their way across

concrete on their knees to ask for miraculous

cures. Inside, masses are

continuously said and people come from all over the world to ask for

intercession to cure their cancers or crippling arthritis. Next to

the basilica stands an older

church, a reminder of colonial days and styles, that is sinking

badly on one side. If

ever a miracle were needed, it would be to keep this church from

looking like it is about to collapse. But,

instead of waiting for a miracle, the folks at this church have

wisely decided to try to hold up the church

with metal braces. On a hill to the east of both churches, stand the

remains of the original church built after the alleged miracle of

Juan Diego's

cloak.

one side. If

ever a miracle were needed, it would be to keep this church from

looking like it is about to collapse. But,

instead of waiting for a miracle, the folks at this church have

wisely decided to try to hold up the church

with metal braces. On a hill to the east of both churches, stand the

remains of the original church built after the alleged miracle of

Juan Diego's

cloak.

About thirty miles from the basilica I had witnessed a group of New Age voyagers on top of the pyramid of the sun at Teotihuacán. About six of them were lying on their backs with their eyes closed, while a woman spoke to them about opening up some door and letting in something or other. "I can feel some of you are blocking," she said. And then she said some other stuff equally uninteresting. I turned my attention to a young man standing near the center of the top level of the pyramid. He was standing with arms outstretched, facing the afternoon sun in the west. He looked content, even if a little sunburned.

Thousands of people had lived in this complex at one time. It is estimated that between 150,000 and 250,000 lived here when the culture flourished, between 150-450 CE. And they built this world without the help of Brahman cattle or horses or an array of indigenous plants conducive to feeding a massive population. If I remember correctly, the only domestic animals they had were turkeys and dogs. Teotihuacán was a major religious center, built in part out of fear of the unknown and an attempt to gain some control over the uncontrollable and unpredictable forces of nature. If we please the gods, the gods will please us. In the end, it seems the gods are never satisfied.

When I was in college during the last century, I remember being taught that the pyramids of Mexico were unlike those in Egypt in that they were not used for burials. Excavations have uncovered burials in the pyramid of the moon, just up the road from the sun pyramid. You learn something new every day, if you're lucky.

The Aztecs also named this place, which had been abandoned in the 7th or 8th century. Teotihuacán means "birthplace of the gods." The first buildings date from around 150 BCE. The pyramid of the sun was completed around 100 CE. There is much speculation about the peoples who founded, built, and eventually abandoned this complex. None of our guides suggested that Teotihuacán was built by space aliens, though. I suspect, however, that in a few hundred years the Diego Rivera mural of the history of Mexico will be declared to have been impossible to have been painted by a Mexican and space gods will once again get credit for something beautiful and wondrous and human to the core.

The mural at the Palacio National in Mexico City was created during the years 1929 and 1945, and survived the devastating earthquake that destroyed a large part of the city in 1985. A miracle? Luck? People will believe what they want. If you are fortunate enough to visit this exquisite work of art, hire a guide to help you identify the dozens of scenes and hundreds of characters. Those who are familiar with the face of Frida Kahlo (Rivera's wife and a brilliant artist) will not need a guide to recognize her in the paintings, and those who know that she had an affair with Trotsky might understand why she is depicted as she is in one panel. Rivera had no love for the Church or clerics and he foresaw a future of socialism for Mexico. Nobody's right about everything. There is a wealth of information and propaganda scattered throughout the mural that a guide can identify for you quickly and painlessly. They're not expensive. Our party of three paid about $8 each for the hour-long tour and we liked our guide, Hugo, so much we hired him to take us to Teotihuacán and the basilica.

I did witness several miracles in Mexico City, however. There are 25 million people living in the city and environs. About six million of them drive cars or buses according to rules that defy codification. It was a miracle every time our driver delivered us to our destination unscathed.

Our final night in Mexico City called for a trip to

L'Opera, a cantina where I was served tequila by a man with

ashes on his forehead, a sign that he had attended an Ash Wednesday

mass and had just begun his Lenten season. While he fasted, our

party gorged ourselves on cheeses, sausages, tortillas, cerveza,

onions, and chilies. When we left, we thought the night was over,

but on our way back to the hotel we encountered hundreds of police

officers carrying plastic shields and automatic weapons. We made our way to the

Palacio

de Bellas Artes, which was barricaded and surrounded by police.

Rumor had it that the president of Mexico was inside having a meal

or something. Soon a demonstrator appeared with a handmade sign that

said the president was a fake. He had a few people chanting but the

police ignored them. We walked around the building for a better view

of what was happening and before we knew it we had tickets to a

dress rehearsal of the Ballet Folklorico that was to begin in about

20 minutes. Soon, we were ushered inside the theater and were

enjoying wonderful dancers in colorful costumes, accompanied by a jaraneros

band playing the same music we had come to hear in Tlacotalpan. Was

this a dream? No, the first set was called "Tlacotalpan" and was a

review by professionals of the same dances and tunes we'd heard

amateurs playing only a few days before. If I were superstitious,

I'd call it synchronicity. I'm not, so I'll just call it grand fun.

If this is what happens when you investigate superstitions, then I

highly recommend it.

We made our way to the

Palacio

de Bellas Artes, which was barricaded and surrounded by police.

Rumor had it that the president of Mexico was inside having a meal

or something. Soon a demonstrator appeared with a handmade sign that

said the president was a fake. He had a few people chanting but the

police ignored them. We walked around the building for a better view

of what was happening and before we knew it we had tickets to a

dress rehearsal of the Ballet Folklorico that was to begin in about

20 minutes. Soon, we were ushered inside the theater and were

enjoying wonderful dancers in colorful costumes, accompanied by a jaraneros

band playing the same music we had come to hear in Tlacotalpan. Was

this a dream? No, the first set was called "Tlacotalpan" and was a

review by professionals of the same dances and tunes we'd heard

amateurs playing only a few days before. If I were superstitious,

I'd call it synchronicity. I'm not, so I'll just call it grand fun.

If this is what happens when you investigate superstitions, then I

highly recommend it.

February 13, 2008

If you enjoyed this article, you might also enjoy Exorcism on Lake Como.

Staying in Tlacotalpan? I highly

recommend

Casa del Rio.

Staying in Mexico City? I highly recommend the

Sheraton Centro Historico. (No, I

wasn't paid to recommend these hotels. They are worlds apart. One is small

and family run, the other is huge and offers all the amenities one could

want. Both are quiet, comfortable, and run by friendly, helpful people.)

Acknowledgement: I must acknowledge our Mexican-American "Jacqui" guide, whose instincts guided us on our journey. She not only made all our travel arrangements, but she intuitively led us to the safety of a boat from a spot that would later be the first place one of the nervous bulls would head. It was her instinct and her ability to ask questions in Spanish and, more important, her ability to understand the answers, that led us to the Ballet Folklorico and a few other places of interest. Thank you, VR, for your valuable guidance and friendship.